When we're tranquil, our minds are like a clear lake. If I were to toss a small stone into such a lake, we'd see it fall all the way to the bottom. With such clarity, we could discover a lost pearl of great price, slipped down to the bottom of this lake. That lake's like our mind, whose muddy waters can become clear and whose ripples flatten out, all on their own. That pearl represents our mind's natural luminosity, solidity, and pricelessness.

This chapter surveys these meditation fundamentals. Square One. Welcome to Base Camp!

Here's Where It Sat:

Posture

Archeologists in the Indus Valley have dug up small figurines of men in the posture of yogic meditation dating back at least five millennia. That's a long time to be sitting. Sure, the sculptor might've been commemorating a sit-down strike or something. We don't know for sure; they didn't come with descriptive booklets. But just looking at them you sense a reverence. It seems almost as if the very posture of sitting cross-legged in the lotus position can mean so much.

In the full lotus, the classic meditation position, each leg's on the opposite thigh. In a half lotus, only one foot rests on the opposite thigh, the other rests on the floor or on the calf, and often with a pillow to support that knee. In a quarter lotus, the feet rest on the calves. And in the Burmese position, both feet are folded in front of your body, not crossed over each other.

For illustrations, please visit Kwan Um School of Zen.

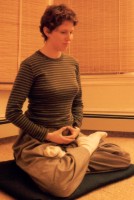

In the accompanying picture (from Kwan Um School of Zen) you see

the classic pose of the Buddha. Have you tried it? Seated, cross-legged, you

aren't going anywhere. The alarm bells of fright-or-flight, hard-wired into

our physiology, always on the lookout for dangers in the environment, get

dimmed way down. Your hands aren't manipulating any tools. There's nothing to

say, nothing to do but sit and breathe, in the here and in the now.

In the accompanying picture (from Kwan Um School of Zen) you see

the classic pose of the Buddha. Have you tried it? Seated, cross-legged, you

aren't going anywhere. The alarm bells of fright-or-flight, hard-wired into

our physiology, always on the lookout for dangers in the environment, get

dimmed way down. Your hands aren't manipulating any tools. There's nothing to

say, nothing to do but sit and breathe, in the here and in the now.

With knees apart slightly, you can meditate while kneeling. You can sit on your heels or a small bench or your zafu on end. If you sit in a chair, don't rely on the back of your chair for support: Rely on yourself, and in good posture.

Just smiling slightly while taking a few breaths can actually make you happier. (Go ahead and try it, right now!) Stopping and taking a few, slow, fully conscious breaths can calm and sharpen awareness. Peace can be as simple and bold as that.

Ears over Shoulders:

Basic Postures

The basics of

meditation have remained the same for millennia. Ideally, you sit on a cushion

on the floor, but a chair works, too. I've heard of someone experiencing

initial enlightenment while sitting in a high school auditorium chair.

On the ground, your legs might take one of three positions: full lotus, half lotus, or Burmese. In full lotus, each foot is on the opposite calf or thigh. In half lotus, only one foot is on the opposite thigh or calf; the other rests on the ground (in which case it's often advisable to put a small, thin pillow underneath it, so both knees are equally level and balanced). Burmese-style, both knees are on the floor. Your contact with the ground should feel like a stable tripod, of knees and sit-space. Feel yourself sink down into this contact, like a mountain upon the earth. Your tailbone makes contact with the ground, and your anus tilts up, along with your hips.

Your back needs to be straight so breathing and energy can flow freely. Imagine there's a small ring at the top of your head, where your hair meets your scalp, and a hook comes down from the sky, engages that ring, and gently lifts you up, as far as your waist. Everything above your waist stretches straight upwards. Your lower back naturally curves in and your upper back naturally curves out. Overall, your spine is erect and stretched. Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder and director of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, points out another way you can imagine this: Sit in a way that embodies dignity. He's noted that whenever he tells his students this, everybody knows that feeling and how to embody it. It's a good practice for throughout the day: remember "dignity," remember "sky hook."At a cafe, when I see people hunched over like Rodin's The Thinker over a sandwich, or a book, or their laptops, I wonder, "Are they getting enough oxygen to their brains, their hearts, their minds?" Bent over, it's hard to breathe fully and so writing, reading, or eating lacks full enrichment. Try it for yourself: Sit hunched over and notice your breathing ~ then notice the difference in your breathing when sitting straight.

Your shoulders are back so your chest can comfortably expand. Your ears are over shoulders. Your shoulders are over your hips. Your nose is aligned with your navel. Your eyes are horizontal with the ground, but you tuck your chin in, which lowers your head just a fraction. (You don't want to squish the back of your brain.) You might imagine your head supports the sky.The state of mind that exists when you sit in the right posture is, itself, enlightenment. If you cannot be satisfied with the state of mind you have in zazen, it means your mind is still wandering about. Our body and mind should not be wobbling or wandering about. In this posture there is no need to talk about the right state of mind. You already have it. This is the conclusion of Buddhism."

~ Shunryu Suzuki Roshi

Your hands can rest on your knees, palms down or up. (More on hands in a second.) Now, test your position. Sway front and back, then left and right. Get centered.

Doing That Cool Hand Jive: Mudras

As the motionless posture of our legs and feet sends a message to our brain (that we're not going anywhere), so too does the placement of our hands hold meaning. An etiquette book, for example, may tell you not to put your little finger out at a 45-degree angle when you hold your fork, so as not to appear "backstairs refined." Two important gestures (called mudras) are those of greeting and meditation.

Hand gestures hold significance. The two-fingered V-sign is almost universal. Buddhism has a catalogue of gestures called mudras (Sanskrit for "sign, seal"). When the Buddha or a deity holds one hand up, palm out, that means protection, "don't fear." Fingers outstretched except the tip of thumb and index finger meeting in a circle is the mudra of teaching. By imitating certain gestures outwardly, it's thought we can cultivate the inner state associated with them.

The two characters ga + sho mean "palms joined."

The two characters ga + sho mean "palms joined."

(Illustration from Jodo Shu)

Joining palms is a universal gesture of spirit. There's a famous etching by Albrecht Duürer of two disembodied hands praying in and of themselves. In the East, putting palms and fingers fully together is a gesture of greeting (namaskar/namastey, Hindu; anjali, Sanskrit; wai, Thai; gassho, Japanese). In India and Thailand, you put your hands together at your chest and raise them to your forehead, often followed by a bow, still in that position ~ eyes and joined hands going outward and down to a spot on the ground equidistant between the greeter and the greeted. It says, "The sacred within me salutes the sacred within you." And "Have a nice day."

More than a salutation, then, it can be an expression of devotion or gratitude, as well as supplication. As the action joins venerator and venerated, it's also an expression of unity, and an appreciation of suchness (see Chapter 8, The Fine Print: Touching Deeper, for more on suchness). It's often used at the beginning and end of meditation. For example, you might to fellow sangha members, and then to your cushion, before being seated. You might also gassho to a statue of the Buddha. (Buddhists also use the word gassho as a salutation in a letter, instead of "Yours truly.")

Cosmic meditation mudra. mahamudra (hokkaijoin, Japanese).

When seated, you can place your palms on your knees. Or you might try the earth-touching mudra, seen in Chapter 1, Why Is This Man Smiling?: The Buddha. But the best is the standard pose, sometimes called the cosmic mudra. Put your the back of your right hand on top of your left palm. Adjust how close or far apart your hands are so your thumbs make contact ever so lightly, at about the height of your navel. From the front, the space between your hands resembles an egg (hold it without dropping it), and behind it is a point below your navel called dan tien in Chinese, hara in Japanese, considered your true center ~ physically in posture, and spiritually as central repository of life-force, also known as (a.k.a.) prana and chi. When you've got the gesture, give yourself two big hands!

Facing Your Meditation

There are about 300 muscles in your face alone. Letting them all relax takes a little time. As you do so, you might ask, "What do I do with my tongue?" Answer: Rest tongue on roof of mouth. Tip to inside upper lip.And why not smile!? Thich Nhat Hanh has coined the nifty phrase "mouth yoga" ~ lifting one corner of your mouth, slightly, like Mona Lisa or the Buddha. He remarks, "Why wait until you are completely transformed, completely awakened? You can start being a part-time Buddha right now!"

To see or not to see!? I like to close my eyes to rest. Seeing is really a very intricate, complex process when you think about it. It uses more than half the space our brain allots for the five senses. Shutting my eyes frees me from all that information, frees me from domination by objects, and directs my sight, instead, inward. Do I need to be aware of the rectilinear borders partitioning space? Eyes closed, I feel rounder and more boundless. Pitfalls to eyes-closed are possibly hallucinating or falling asleep.

Some zen teachers suggest keeping your eyes open, keeping this-worldly. (After I've checked in at Base Camp and feel calm, I usually do open my eyes for the duration of my meditation.) For that route, try focusing your gaze on a spot on the floor about a yard away. If you're in a group, the back of the person in front of you would do.

What If I Froze Like This?:

Warm-Up Stretches

It can be

hard enough just sitting for 45 minutes without composing a stunning speech to

your lover or manager. But, as Oscar Wilde exclaimed, "Spare me physical

pain!" That is, part of your job is to note the arising and passing of

physical distractions as well as the mindwaves, without judgment, and to let

them go. On a retreat, people often notice both physical and mental pain

falling away at or after the third day. But, on the other hand, you're not

inviting pain. So, as with any athletic physical culture, warm-ups are a sound

investment in a healthy, happy practice.

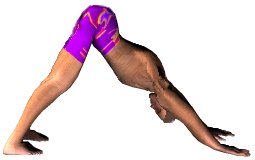

Check out The Complete Idiot's Guide to Yoga for information on such poses as the Bound Angle, the Butterfly, the Cat, the Cobbler, the Cobra, the Cradle, the Downward Dog, the Hero, the Locust, the Lunge, the Supported Bridge, and the Triangle, and The Complete Idiot's Guide to Tai Chi and Qi Gong for Tai Chi warm-up exercises, all of which make excellent stretches for meditation.

Yoga instruction in such poses as the downward-facing dog and help keep the pain demons

away from meditation sessions, and make you more feel human afterward.

Yoga instruction in such poses as the downward-facing dog and help keep the pain demons

away from meditation sessions, and make you more feel human afterward.

~ return to top

Why Not Breathe?

You're Alive!

No matter the spiritual tradition, breath's an essential ingredient. What could be more impermanent and insubstantial, yet vital and universal? In the biblical creation story, human beings were fashioned out of red clay and infused with the divine breath of life. It's interesting that the word used in the New Testament for spirit literally means breath. Thus in John 20:22, "Receive thou the Holy Spirit," the original is literally, "Receive holy breath."

From cradle to grave, we're breathing ~ but we're seldom aware of it. So why not check in for a moment? When you're ready, set this book aside, and just notice your breathing. Like a mental snapshot, a breath impression. Just pay some attention to how you're breathing. Don't judge. Don't try to change anything. Three or four breaths later, notice if you feel any more centered, grounded, for having checked in. That's all it takes. Try it.

I don't know if Jesus taught his disciples conscious breathing, but it's an interesting notion. (Consider Acts 2:4, for example, "And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit" ~ filled with holy breath; perhaps also filled with the awareness of the holiness of breath?) Christians who practice Buddhist conscious breathing sometimes call it "resting in the Spirit." Meditating on breath brought Siddhartha to Grand Enlightenment. And so he specifically addressed conscious breathing from the very start. His Sutra on Full Awareness of Breathing is one of his most essential teachings.

The Sanskrit word for breath, prana, also means universal energy, life-force. The origin of the Chinese word for this, chi (pronounced chee, also spelled qi), is believed to be steam, vapor. The word spirit come from Latin, spiritus, spirare, meaning breath; to breathe. (Inspiration means breathing in.) The Old Testament Hebrew and Greek words for spirit, ruach and pneuma, mean breath but also wind (merging within and without).

Breathing's universal and ever-present. Everybody breathes, and all the time. And it's integral to our state of being. Thus it's a perfect vehicle for practice.

One-breath meditation can be a base upon which to expand. See what feels right. Add five minutes ... then try ten. It's kind of awesome to be aware of breath, and nothing else. Interesting, at least. You already have all you need for conscious breathing. So play with incorporating it as part of your practice.

Some people slide right into it, while others need a little hand-holding. So a few pages follow with some techniques to help center or guide your awareness. Read through and see if just one might sound interesting. Trying them all right now might be overkill. They're all designed to focus awareness on breathing and set aside anything else. For example, you might loop a string of beads around your hand and move one bead down with your thumb each time you've breathed in. (Works for me!)

Three more such mindful breathing techniques are as follows:

- Body

- Counting

- Mantras and gathas

Having a Gut Feeling That the Nose Knows

Two areas of your body can help center your mind on your breathing ~ and then help your breathing center your mind. You can focus awareness on either your nostrils or your navel.With your mouth closed, your breath comes and goes through your nostrils. Rediscover this for yourself. Sitting still for a moment, right now, be conscious of that fact. When you're ready, put this book aside. You might direct your attention to the very tips of your nostrils. Breathing in, feel how cool breath can feel at your nostrils ~ maybe even how fragrant. Breathing out, feel how warm the breath feels at your nostrils ~ warm and fuzzy, perhaps.

That's meditation bedrock, for many; all that's needed. But your mind might naturally expand and want to explore. If so, you might direct your attention to your breath coming and going through your inner nostrils. And stay with that. When you can do that, and just that, for five minutes, congratulations! ~ you've established your meditation base camp.

Consider conscious breathing your base ~ from which to set forth, and explore, and to which you can come home. It's that center or "centering" you might hear about in spiritual circles. Maintain it with regular practice. Build upon it if you like by adding five minutes, until you're up to 30 to 45 minutes a day.

Alternatively, you can concentrate on your navel. Maybe you've heard the stereotype of Eastern meditations as being "navel-gazing." Actually, it's not the navel but the hara or dan tien that you focus on. It's about the size of a dime, three or four fingers down from the navel. If our nostrils are the doorway, then this might be thought of as the palace basement, the storehouse, the secret treasury.

Focus on belly breathing may run counter to the way you've been brought up. I know I was taught to keep my abdomen hard, military-style. "Hold it in," the expression went, and, since body and mind are one, this applied to emotions as well; aren't they often called "gut feelings"? So it's not uncommon to see people trying to breathe deeply by expanding their chest rather than their bellies. When frightened, babies breathe in their chests, as if scared of contracting something overwhelming in their belly. Some people often carry this trait over into adulthood as a basic policy toward life. ("Uh-oh, this makes me breathe deeply: Houston, we have a problem.") Notice how far down your body moves with your own breath. Don't try to change or judge it. Just observe.

Concentrating on your lower tummy instead of your nose, be aware of how your belly fills when you inhale, and falls when you exhale. As you do so, feel any hardness in your belly gradually soften, breath by breath. Breathe into any tightness in your belly. Exhale any tensions this might release. (Ahh!)

After a few sessions of conscious belly breathing, you might find your breathing fills your belly more than before, automatically. If so, just notice it. If not, no sweat. Breath eventually deepens of its own. Belly awareness creates conditions that can assist the process. This is the Buddha's way ~ providing the nourishment for seeds to become flowers.

Note: This isn't yoga. That is, you aren't trying to control your breath, nor make it any different than it already is. Your job is to just watch it. It may seem like a paradox: controlling the breath to control the mind, without controlling anything, just observing. But that's the name of the game. Try and control the mind, and it becomes even harder to tame, like a wild horse, or a child throwing a tantrum.

And these are just training wheels. Your meditation's not about nose or tummy (not to mention the parameningeal epigastrum). Basic meditation is about letting body, mind, and breath get reacquainted, and watching these old friends work together.

Making Each Breath Count

Counting's another way to focus awareness on breath, and keep your mind from wandering. Try this: calmly breathe out, say to yourself "one," then breathe in that "one," and breathe out, and begin "two." Don't think of anything else but your breath. Just your breathing in, your breathing out, and then a very quick, light count. And nothing else. At "four," return to "one," again. If your mind wanders, as it does, begin all over again, at "one."Here are two open secrets about counting. 1) You're not an idiot if you can't make it all the way to four. But if you can do four sets of "four," simple as 1-2-3, then just observe your breath without counting. 2) You don't have to feel like an idiot to return to such simplicity as 1-2-3-4; these are basics of life. Buddhism means back to basics.

Remember, keep your attention on your breathing, not the count.

Words to Meditate by:

Mantras and Gathas

Besides

body awareness and counting, two more options for focusing awareness on

breathing and quieting the mind are verbal:

- Mantra

- Gatha

One mantra many people use when beginning conscious breathing meditation, is mentally saying to themselves "IN" while breathing in, and "OUT" while breathing out. Concentrating on each word focuses the mind on breathing. In. Out. One single word for one single breath. Some people mentally recite them "in-in-in" and "out-out-out."A mantra (mohn-trah) can be a word or phrase repeated to aid our memory. Thus when we repeat the Buddha's name, we're remembering him. They can also symbolize and communicate a certain energy or deity, as well as erase bad habit energy by substituting positive consciousness. Mantras can be recited aloud or mentally. Hindus might chant, "Om." Christians, "Amen" or "Alleluia." Muslims, "Allah." Jews, "Shalom." (However, Jimmy the Greek says you should take firm control of your spiritual destiny: don't leave anything to chants.)

A gatha (verse) attributed to the Buddha is:As a solid rock stands firm in the wind(That is, unshaken by ordinary affairs.) A gatha by Zen patriarch Dogen:

Just so the wise are unmoved by praise or blame

Realization, neither general nor particular,

is effort without desire.

Clear water all the way to the bottom;

a fish swims like a fish.

Vast sky transparent throughout;

a bird flies like a bird.