Jiufeng’s “One Who Transmits Words”

Dharma Discourse by John Daido Loori, Roshi

Master Dogen’s 300 Koan Shobogenzo,* Case 221

Featured in Mountain Record 19.4, Summer 2001

The Main Case

Priest Jiufeng was once asked by a monastic, “I heard that you said that one who transmits words is outstanding among the sages. Is it true?”1 Jiufeng said, “That’s right.”2 The monastic said, “Shakyamuni emerged in this world, pointed to heaven and earth, and said, ‘Above earth and under the heaven, I alone am venerable.’ How can you call him one who transmits words?”3 Jiufeng said, “I call him one who transmits words because he pointed to heaven and earth.”4[View Footnotes] The Great Master Bodhidharma said, “Zen is a special transmission outside the scriptures, with no reliance on words and letters.” Master Jiufeng said, “One who transmits words is outstanding among the sages.” The visiting monastic came seeking clarification on this matter. He did not yet understand that language and activity are one reality. Sutras, koans, words, silence, the cooing of an infant, images, gestures, right action, the sounds of the river valley and the form of the mountain are all expressions of the buddha nature in absolute emptiness. Jiufeng said, “I call him one who transmits words because he pointed to heaven and earth.” I say that even insentients transmit words. These mountains and rivers themselves are continually manifesting the words of the buddhas and ancestors. Indeed, if we examine this teaching carefully, we see that all of the phenomena of this great universe — audible, inaudible, tangible and intangible, conscious and unconscious — are constantly expressing the truth of the universe of the buddha nature. Do you hear it? Can you see it? If not, then heed the instructions of the Great Master Dongshan and “see with the ear, listen with the eye.” Only then will you understand the ineffable reality of the word.The Commentary

The Capping Verse

Summer pond, silent and wordless,

naturally opens a path.

Even Shakyamuni didn’t understand it.

How can anyone transmit it?

Footnote: *300 Koan Shobogenzo is a collection of koans gathered by Master Dogen during his study in China. The koans from this collection, often called the Chinese Shobogenzo, appear extensively in the essays of Dogen’s Japanese Shobogenzo. These koans have not been available in English translation but are currently being translated and prepared for publication by Kazuaki Tanahashi and Abbot John Daido Loori. Abbot Loori has added a commentary, capping verse, and footnotes to each koan.

Even though Dogen did not choose to elaborate on this koan in the

Shobogenzo, it is still an important case to take up because it points to our

conventional and limited use of language, and it contrasts this use with Dogen’s

unusual way of expression. Dogen used language radically, turning upside–down

many of the Buddhist concepts that had become stale in Zen. When Bodhidharma

made the statement, “Zen is a special transmission outside the scriptures, with

no reliance on words and letters,” he was referring to the fact that Zen does

not depend on words to express the nature of reality. Unfortunately, some

practitioners misconstrued this statement to mean that words have no value in

the buddhadharma. Consequently, there are Zen monasteries and centers where

reading is strictly forbidden and books are kept under lock and key. Dogen was

vehemently opposed to this limited view of practice. He was not only open to

using language as a way of teaching, but he also recognized that the symbol, in

this case the word, and the symbolized are one reality.

Even though Dogen did not choose to elaborate on this koan in the

Shobogenzo, it is still an important case to take up because it points to our

conventional and limited use of language, and it contrasts this use with Dogen’s

unusual way of expression. Dogen used language radically, turning upside–down

many of the Buddhist concepts that had become stale in Zen. When Bodhidharma

made the statement, “Zen is a special transmission outside the scriptures, with

no reliance on words and letters,” he was referring to the fact that Zen does

not depend on words to express the nature of reality. Unfortunately, some

practitioners misconstrued this statement to mean that words have no value in

the buddhadharma. Consequently, there are Zen monasteries and centers where

reading is strictly forbidden and books are kept under lock and key. Dogen was

vehemently opposed to this limited view of practice. He was not only open to

using language as a way of teaching, but he also recognized that the symbol, in

this case the word, and the symbolized are one reality.

In his fascicle “Painted Cakes” he said, contrary to what Zen Buddhists had insisted for hundreds of years, that painted cakes do satisfy hunger. In fact, he insisted that aside from painted cakes there is no way to satisfy hunger. “Painted cakes” are the images or symbols we have for reality. Until Dogen, Zen Buddhists said that only reality itself would ever satisfy us. Dogen countered: “Except for the pictured cakes there is no medicine for satisfying hunger. You do not encounter human beings unless your hunger is the pictured hunger, nor do you gain energy unless your satisfaction is the pictured satisfaction. Indeed, you are filled in hunger and feel satiated in no hunger. You do not satisfy hunger nor feel satiated in no hunger. You do not satisfy hunger nor do you gratify no hunger. This truth cannot be understood or spoken of except in terms of the pictured hunger.”

This nondual conception of a picture and reality is fundamental to Dogen’s way of thinking and teaching. That’s how he arrives at the truth that painted cakes alone can satisfy hunger. To put it differently, unless we eat pictured cakes, we can never satisfy our hunger. But, what is it to picture something? Where is the picturing taking place?

Dogen didn’t reject creative imaginings and artistic creations as being unreal or fictitious, any more than he discarded the empirical reality of the senses. He was saying that it’s of utmost importance not to believe in either imaginings or reality at the expense of one another, but to understand both of them as being nondual and undefiled.

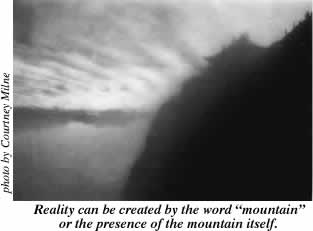

Reality can be created by the word “mountain” or the presence of the mountain itself. In Buddhism we talk about six senses: seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and thinking. Ultimately, mind is where reality takes shape. Whether a reality is triggered by a word, a gesture, a shout, or a physical entity makes no difference whatsoever.

I added footnotes to clarify this case. Priest Jiufeng was once asked by a monastic, “I heard that you said that one who transmits words is outstanding among the sages. Is it true?” Footnote says, He thinks there must be an error here. Jiufeng said, “That’s right.” The footnote to that comments, The old man confirms his own heresy. The next line: The monastic said, “Shakyamuni emerged in this world, pointed to heaven and earth, and said, ‘Above earth and under the heaven, I alone am venerable.’ How can you call him one who transmits words?” The comment is, These words have resounded for eighty-four generations, and still he believes it’s wordless. The last line: Jiufeng said, “I call him one who transmits words because he pointed to heaven and earth.” Footnote: For this old teacher, throughout the whole universe everything is food.

The commentary reads, The Great Master Bodhidharma said, “Zen is a special transmission outside the scriptures, with no reliance on words and letters.” Bodhidharma was an Indian monk who lived around 500 CE, and is considered to be the First Ancestor of Zen. His pithy stanza also includes a description of Zen as “a direct pointing to the human mind and the realization of buddhahood.” There are all kinds of ways that direct pointing happens, and it can arise both among the animate and the inanimate, in speech and in silence.

Master Jiufeng said “one who transmits words is outstanding among the sages.” The visiting monastic came seeking clarification on this matter. He did not yet understand that language and activity are one reality. Sutras, koans, words, silence, all speak eloquently under the proper circumstances, but there must be a mind to receive them. In his poem, The Mirror of Samadhi, Master Dongshan attempted to describe thusness or suchness, this-very-moment-as-it-is, in all its perfection and completeness. He used many beautiful words trying to convey this instant of reality. At the end of the poem he exclaims “baba wawa”. When I first read this I had no idea what it meant so I asked my teacher. He said that it was the cooing of an infant. That cooing is the expression of this incredible Dharma, of the buddha nature. It’s no different than the song of a bird, the sound of the wind in the pine trees, Rinzai’s shout, or Buddha silently holding up a flower on Mount Gridhrakuta. Something must have been manifested when Buddha raised the flower because Mahakashyapa got it. It wasn’t until after Mahakashyapa had gotten it and smiled that the Buddha announced for the benefit of the rest of the assembly, “I have the all-pervading Dharma, the exquisite teaching of formless form. It is transmitted outside the scriptures. I now hand it over to Mahakashyapa.” First, Buddha held up a flower and blinked his eyes, Mahakashyapa’s smiled and the transmission was complete. Then, the announcement was made.

The commentary also mentions right action as expression. When you respond to the need of someone; when you speak loving words; when you dispense medicine to heal the sickness, you are expressing the truth of the universe, of absolute emptiness.

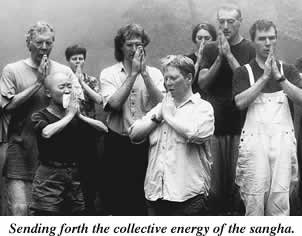

Here at the Monastery we chant dharanis during our daily services. We chant sounds that have absolutely no meaning. Dharanis are made up of pure sounds. In order to appreciate why we chant them we need to understand the relationship of sound to consciousness. When you have the flu, with your body racked with pain and miserable, making the simple sound “ooooooooh” feels good. It somehow couples with your consciousness and it eases the pain. The syllable Om centers you and stills your mind. When you’re feeling great, on top of the world, “yeeeeeah!” is an expression of that joy. These sounds directly affect our consciousness. When these sounds or mantras are linked together in chanting they create a dharani, which literally means spell or magical incantation. The Sho Sai Myo Kichijo Dharani, which we chant every day as part of the morning service, is a healing dharani, and it’s dedicated to people who are suffering life-threatening illnesses. It’s a way of sending forth the collective energy of the sangha to people in need of support and healing.

In the early eighties, when I mentioned this healing energy

people would snicker. Nobody doubts anymore because there’s been a lot of

research done on the relationship of the mind to healing. In one experiment,

number of patients were prayed for by people around the country. Patients did

not know if they were in the healing group or in a control group. The people who

prayed did not know the patients and sometimes were hundreds of miles away. It

didn’t matter what their religion was; they just had to pray for the person who

was ill a couple of times a day. The results were remarkable. The people who

were prayed for recovered faster and more completely than the ones who weren’t

prayed for. Obviously, there’s a lot more to human consciousness than we have

even begun to understand.

Finally, the commentary turns to the sounds of the river valley. Dogen calls these sounds the eighty-four thousand hymns. The sounds of the river valley and the form of the mountain are all expressions of the buddha nature in absolute emptiness. In the opening words of “Mountains and Rivers Sutra,” Dogen says, “These mountains and rivers of the present are the actualization of the word of ancient buddhas.” Some translations use “way” instead of “word.” I think “word” is a lot more appropriate because Dogen specifically calls this fascicle a sutra — the words of the Buddha. The mountains and rivers are the teachings of the insentient. Rocks, trees, the wind, the ocean, are constantly manifesting the Dharma.

Jiufeng said, “I call him one who transmits words because he pointed to heaven and earth.” Many times during my training, I sat in front of my teacher at the edge of seeing something. I would ask him and wait for an answer. But he gave me nothing: not a smile, not a twinkle in his eye, not a snort, not a quiver, and yet BAM! I would see it; I would get it. When you are open and receptive in your asking; when you’re alive and alert, everything is constantly teaching, everything is constantly nourishing. These mountains and rivers are continually manifesting the words of the buddhas and ancestors. Indeed, if we examine this teaching carefully, we’ll see that all phenomena — audible, inaudible, tangible and intangible, conscious and unconscious — are constantly expressing the truth of the universe. Sometimes you can’t hear or see it, but they’re expressing it. When you look for it, it can’t be grasped, and yet it comes home.

Most of us go through our lives oblivious of these teachings because our minds are filled with information. Ironically, it’s because we’re so educated and sophisticated that we don’t have space to receive the teachings of the insentient. We constantly talk to ourselves. How can we hear anything else? Yet, when the mind reaches the still point; when it comes home to the ground of being and we open up, we see there’s a chorus of teachings that will nourish, heal, clarify, and awaken us. At times we learn unconsciously because what’s being taught is communicated in a way we don’t expect. But the fact is that it is not even communicated. The Dharma is not transmitted. There’s nothing that goes from A to B. There’s nothing that Buddha had that you don’t already have. That’s why we call realization “the wisdom that has no teacher.” Everything is already in you. The dharani, the shout, the mantra, the pointing, the koan, the sutra, the gesture are devices that awaken that which is already there.

The commentary ends, Do you hear the teaching? Can you see it? If not, then heed the instructions of Master Dongshan and “see with the ear, listen with the eye.” Dongshan had read this phrase in the Avatamsaka Sutra. The National Teacher repeated it, Guishan echoed it, and then Dongshan went to his teacher, Yunyan, and said “Is this true?” Yunyan said, “Yes, the insentient are constantly teaching.” Dongshan asked, “Do you hear it, teacher?” Yunyan replied, “No, I don’t hear it. If I heard it, then you wouldn’t hear my teaching.” What was he saying? All of the teaching in Zen is constantly pointing to intimacy.

In order to hear the insentient’s teaching, you need to be the insentient. You need to be intimate with it. That’s what it means to see with the ear, to listen with the eye. It means to see with the whole body and mind, to hear with the whole body and mind. It’s not about processing information; it’s not about analyzing, judging, categorizing, figuring it out. It’s about intimacy. In intimacy, there are no gaps, no separation, no this and that. So, see with the ear, listen with the eye. Only then will you understand the ineffable reality of the word.

The capping verse: Summer pond — silent and wordless, naturally opens a path. It opens a path without doing anything, just by virtue of its existence. During the spring, the pond is full of noise and activity: toads, spring peepers and bullfrogs mating, ducks feeding, fish hatching their eggs. But sometime in the middle of the summer, everything stops and the water gets very quiet. You know the pond is alive because its surface still quivers a little. You know there’s life underneath, but there are no sounds, no words. In this stillness, a path opens and a clear way is made.

Even Shakyamuni didn’t understand it. How can anyone transmit it? It’s not about understanding. It’s not about believing. And the reason no one can transmit it is because it’s already there. You carry it around with you. You’re born with it and you die with it. In spite of its presence, we go through a life of hell, confusion and craziness. But underneath our conditioning is a Buddha.

Zen practice is a way of getting to that ground of being, a way of realizing for ourselves what the Buddha realized, what thousands of Buddhist men and women have realized over 2,500 years: the inherent perfection and completeness of each and every one of us. Further, we need to not only realize it, but actualize it. We need to bring it out into our life, to manifest it in everything we do, from the way we live and relate, to the simple activities of taking a meal, sweeping a garden path, raising a child, growing a garden. Ultimately, that’s what the whole thing comes down to. That’s what it means to give life to the Buddha. It means to practice, realize, and actualize. We have the whole phenomenal universe working in concert to help us do that. We should wake up and hear it, see it, be it, feel it, and practice it.

1. He thinks there must be an error here.

2. The old man confims his own heresy

3. These words have resounded for eighty-four generations, and still he believes it’s wordless.

4. For this old teacher, throughout the whole universe everything is food.

John Daido Loori, Roshi is the abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery. A successor to Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi, Roshi, Daido Roshi trained in rigorous koan Zen and in the subtle teachings of Master Dogen, and is a lineage holder in the Soto and Rinzai schools of Zen.

[Main Case] [Index of Dharma Discourses] [Table of Contents] [Subscription Information]

©2003 Zen Mountain

Monastery

mountains & rivers order | training in the mro |

zen mountain monastery | fire lotus zendo |

dharma communications | zen environmental studies

institute | society of

mountains & rivers | the

monastery store | wzen.org | contents | contact us |

All words and images on these pages are protected by

copyright