|

The Heart Sutra Sesshin talk

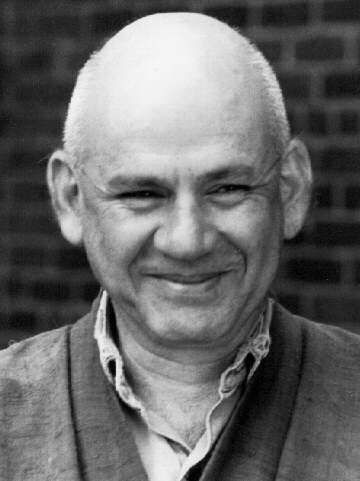

given by Sojun Mel Weitsman |

Well, this is the third day of sesshin. Sesshin has a way of taking care of us in that something will drop away by itself and clarity will come by itself; and even though there may be some confusion in our mind, there is also clarity. So I am going to go on talking about the Heart Sutra. "Oh Shariputra, all dharmas are marked with emptiness." Before the first century, we count eighteen schools of Buddhism, and there were probably more; the eighteen are what is recorded. These eighteen schools each took a different position on various issues of doctrine, and there were controversies between them as to what was the correct attitude toward life, and other matters. |

|

One of the arguments was about dharmas. It was pretty much the case that all of the schools agreed that there was no "self" (that what we call a self was not a self). There was a school of so-called Pudgalavadins who leaned toward believing that there actually was some permanent soul-like substance, or spirit, which actually transmigrated from life to life, but that was the only school of Buddhism which had that idea. All the other schools of Buddhism said there was no self. There were just form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness [the five skandhas], and those didnít constitute a soul. Then there was a controversy over dharmas. Some schools thought that there may be no soul, but that dharmas actually did exist. Dharmas are like the elements that make up everything, but here we are speaking of them as making up a person. They thought that, even though there is no substantial person, at least the elements, the dharmas, exist. Then the Mahayana school came along and said that even the dharmas are empty, so, there is no self, and there are also no dharmas that have their own substantial existence. Anyway, in the Sutra Avalokitesvara says, "Oh Shariputra, all dharmas are marked with emptiness," and the skandhas are as well. "They do not appear nor disappear." Now, this is a strange statement! Things "appear" and "disappear." But here we are talking about the phrase "in emptiness." In the sutra everything is referred to as being "in emptiness." So, in emptiness things do not appear nor disappear: although something comes along, its true nature doesnít come or go. There is only transformation, and, in the realm of transformation, things appear and disappear, but the true form of things doesnít appear or disappear. True form is no form, no special form, and, out of this "no special form," all of the special forms take shape. Then the Sutra says, "...they are not tainted nor pure." They are neither tainted nor pureÖ.As I said the other day, we are always dividing things into pure and impure, tainted and pure; the pure life, the dissolute life, the pure dharmas, and the impure dharmas. Pure dharmas are the good dharmas, all the things that we do that lead to wholesomeness, and the impure dharmas are all the bad things that we do. Yet, there is nothing that is really tainted or pure in itself. Something is only tainted in relation to something that is good, and not tainted; and something is not tainted in relation to something that is tainted. In themselves they are not tainted or pure. If you were to ask the decaying grapefruit rind, "Are you tainted or pure?" It would say, "What are you talking about? I am just myself. I am just this old, rotting grapefruit rind. I am neither tainted nor pure." Itís just your perception that makes tainted or pure. In reality things are not tainted nor pure, yet we live in a world of purity and defilement, and we have to pay attention to purity and defilement. So we discriminate and say, "this is good and this is bad; this is right and this is wrong." Thatís okay, but we have to realize that, in an absolute sense, itís not right or wrong, and itís not tainted or pure. So how should we discriminate? Itís all based on whether or not we are self-centered. Our discriminations are usually based on selfcenteredness. I like this, and I donít like that. This is good, and thatís not so good, according to what I like. That is self-centered. But if we get off of the self as a center and take Buddha as the center, then, instead of being self-centered, we are Buddha-centered or Buddha-centric. Then we can see from the point of view of Buddha rather than from the point of view of myself or our self. From the point of view of Buddha, there is no duality, or the duality exists within the nonduality. So we would have to base our decisions, and our distinctions, on non-distinctions, or base our discriminations on non-discrimination. This process is actually called "the discrimination of non-discrimination," a kind of contradictory thing if you are looking at it in a dualistic way, but it is not dualistic from a Buddhist point of view. When we take ourselves out of what it is that satisfies this person and look at the bigger picture of how does something work, then our discriminations are based more on what is taking place within the situation, rather than being based on our being in the center of the situation. For example, when you are having a meeting with ten people and a subject comes up, some people are discussing the subject and are speaking from the point of view of their own desire. Someone else may be speaking from the point of view, not of their own desire, but of how the situation could be made to work, whether it does them any good or not, or whether it pleases them or not. This is discriminating on the basis of nondiscrimination. Suppose you are in this discussion with these people and it turns out that your vote will put you in a position "out in Siberia" because itís the best thing for everyone else, however you vote. If your decision is based on nondiscrimination, if your discriminating decision is based on not-self or non-discrimination, then you will see what is best for everyone else, and, even if it puts you off by yourself somewhere, thatís the way you will vote. But we donít usually do that. Most people will vote to put themselves in the best position. So the Bodhisattva always take the correct position according to the situation rather than putting himself into the center of things. Then the sutra says dharmas "do not increase nor decrease." Everything is just what it is. Things change and develop; development is constant. Dogen says, "Firewood does not turn into ash." Firewood is firewood, and it has itís "before" and "after." Next there is ash, and ash is the result of firewood in some way, but firewood is firewood and ash is ash. If you ask ash, if you could say to ash, "Once you were firewood, did you know that?" The ash would say, "What are you talking about? I donít know anything about firewood." So everything, all of us, have a past, an evolutionary past, but, actually, we donít think about that. We just think about what is happening now, and if someone told us about what we were in the past (maybe we were a rock in a forest), you would say, "Oh, come on! How could that be?" But ash says, "What do you mean I was a piece of firewood? What are you talking about?" So, in that sense, everything is just what it is. But, on the other hand, there is development from causes and conditions of one thing into another. So both views are necessary, both that things appear the way they are, and that, at the same time, there is constant evolution. "Therefore in emptiness, no form, no feelings, no perceptions, no formations, no consciousness." These are the skandhas. "No eyes, no ears, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no color, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no object of mind; no realm of eyes, until no realm of mind consciousness." As I said before, these are the eighteen elements with which we perceive the world. We perceive through the eye, we perceive through the ears, the nose, the tongue (the "body" means touch), and these are the doorways of perception. Then, there is no object of mind, which is the thing you are seeing; no color, which is the object of the eyes; no sound, which is the object of the ears; no smell, which is the object of the nose; and no taste, which is the object of the tongue; and no touch, which is the object of the body. No object of the mind. Then comes "no realm of eyes," and "no realm of mind consciousness." In order to see, there has to be an eye, something seen, and there has to be consciousness. The same is true for hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, and thinking. There has to be an object for thinking before there is thought and a consciousness. Master Tozan, when he was a little boy, said to his teacher after reciting the Heart Sutra, "But I have a nose, I have eyes." This is a question that comes up for most people after reading the sutra. "I have a nose, why does the sutra say no nose?" His teacher said, "You are pretty smart boy, you should go see a Zen master." Soon he started studying Zen. What the Sutra means is that the nose doesnít exist independently. The point that the sutra is trying to make is that the phrase "in emptiness" means "in interdependence." Everything depends on everything else. The nose is a nose, but the nose is also the whole universe. The ear is the ear, but the ear actually is the whole universe. The ear does not exist independently from the whole universe. It takes a whole universe to create an ear. Therefore in emptiness, in interdependence, there is "no ear," but "no ear" means that, at the same time, there is an ear. The ear is not an ear. What is it? Thatís a koan. The ear is not an ear, what is it? "You" are not a "you." What are you? So thereís one basic koan, "Who are you?" Not "what is your job?" or "who is your mother?" but, "what are you? who are you?" You only know who you are when you can forget yourself completely. "...no taste, no touch, no object of mind, no realm of eyes, until no real of mind consciousness." This line refers to going beyond consciousnessÖ"and no realm of mind consciousness." In Mahayana Buddhism we speak of eight levels of consciousness. There are the consciousnesses of the five senses, and the sixth one is mind consciousness, manuvijŮana. "VijŮana" means consciousness. Mind consciousness is the thinking mind, but, in particular, it is the discriminating mind, mind which discriminates between the realms of sense and says, "this is seen, this is heard, I hear this, I see this, I taste this," and so forth. Otherwise, if we didnít have the discriminating mind, we would eat something and we would say, "Oh, this apple hears really well or... I see this apple crunch." You know, we should be able to do that, we should be able to see through the ear. But I donít know anything about that. There is something else that Master Tozan said, "Only when you can see it through the ear and hear it through the eye will you know it intimately." So, there is the sixth consciousness, which is the thinking mind, and, then there is the seventh consciousness which is called manas. I will talk about that after I talk about the eighth one. The eighth consciousness is called alaya-vijŮana, the storehouse consciousness, which stores all the memories and knows everything that we have ever done or thought. Itís the storehouse of the seeds of our actions and thoughts, and it doesnít have a mind of its own; it doesnít discriminate good and bad. It just collects everything. The impressions of all of our actions and thoughts are stored there, and every time we do something a seed is deposited in the alayavijŮana. When the seeds are watered, they sprout and produce another action or another thought of a like kind. So this is the source of our "habit energy" or habitual way of doing things. When certain conditions come about, these conditions awaken the seeds and then we do something over again. So this alayavijŮana is like a constant turning, continually producing new results (the seeds are continually sprouting), directing our activities along with our thinking mind. Because of our karma, our volitional actions, we think and act in a certain way. The sprouting of the seeds that are stored, according to the conditions we meet, causes us to have a certain kind of personality and to think a certain way and act a certain way over and over again. It is hard to get out of that cycle. The seventh consciousness is called manas, and the function of that consciousness is to send messages between the alayavijŮana and the thinking mind or consciousness. It takes over and becomes the center. It can become inflated, and is called the ego-consciousness because it mistakes the alayavijŮana for itself and creates the idea of a separate existence instead of sending messages, instead of just performing its function of seeing everything as it is. It creates a scenario about what life is about and sees itself as a separate being, and thatís called "ego." When we talked about getting rid of ego, what we were talking about was transforming the manas consciousness, the seventh consciousness, into wisdom. In the practice of Mahayana Buddhism, when the consciousnesses are turned, they are called "wisdoms," and before they are turned they are called Ignorance. When manas is turned into a wisdom, it is called the Great Mirror Wisdom which sees everything just as it is, without distortions. Ego, by way of contrast, is always distorting and seeing the world from a perverted and partial point of view. So we can say that ego is partiality. It is a distorted view, and it takes itself as the center. I think of it sometimes like the office boy who goes into the bossí office and opens the cigar box, takes out a cigar, sits in the bossí seat and puts his feet up on the desk. He answers the telephone when the boss is out, and locks the door so the boss canít get back in. Mind consciousness is a big subject in Buddhism....(to be continued) © Copyright 1998, Sojun Mel Weitsman | |